Rochester City Hospital opened in February 1864 and from the beginning admitted furloughed soldiers as patients. Although only St. Mary’s Hospital was designated as a U.S. Army General Hospital, both St. Mary’s and Rochester City Hospital treated local wounded union soldiers. Federal funding of $5.50 per week compensated the hospitals for treating wounded soldiers and in 1865, this revenue accounted for seventy-five percent of the City Hospital’s income.

Army Medical Corps

By the end of the war, the U.S. Army had developed a well-organized medical corps comprising a system of levels of treatment starting at Regimental Dressing Stations where minor wounds were treated and triage was performed before transfer to Division hospitals. Depending on the severity of the wounds, patients were transferred to Division and Corps Hospitals for surgery or treatment for disease. Casualties requiring extended treatment were evacuated to theater based Army Depot Evacuation Hospitals or to larger Army General Hospitals. To make room for new casualties, many patients were furloughed back to their homes for recuperation or prolonged treatment in civilian General hospitals such as St. Mary’s and the Rochester City hospital. The great majority of Civil War deaths were the result of disease rather than combat wounds.

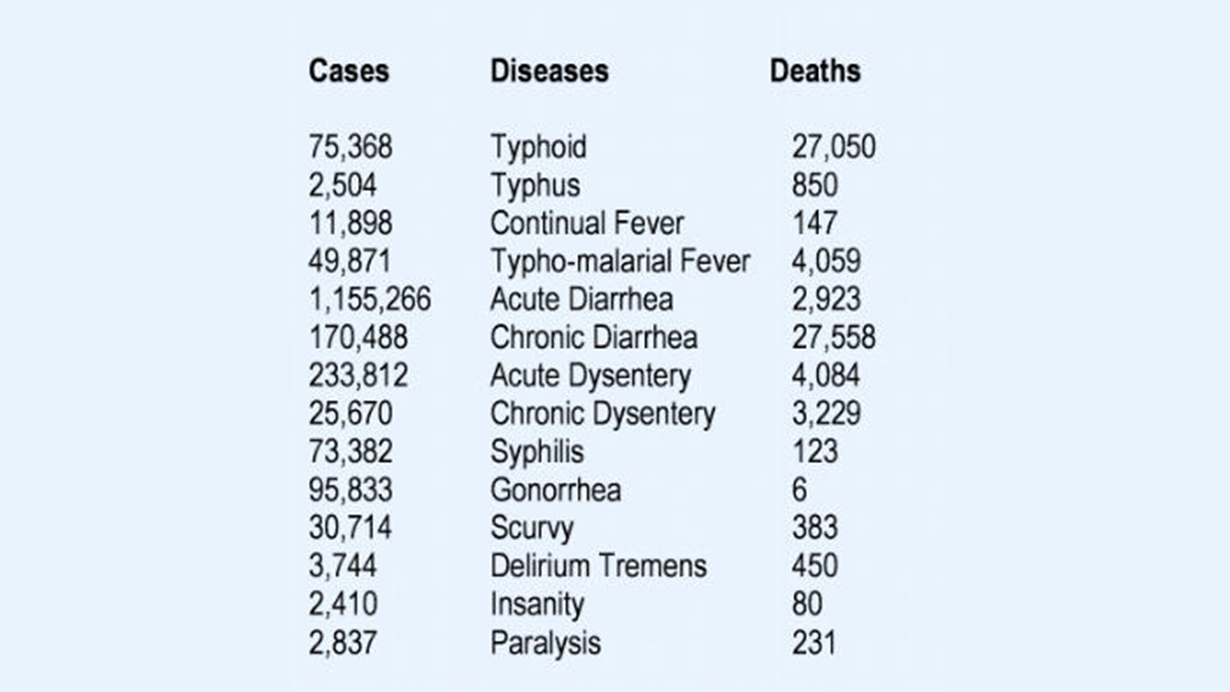

Threat from Disease

In the Civil War, Army surgeons treated a wide spectrum of illness as well as performed advanced surgical procedures. Of the 618,000 reported deaths from both the Federal and Confederate forces during the four years of war, 414,000 were the result of disease. Poor diet, lack of proper clothing, and equipment, and unsanitary conditions contributed greatly to the deaths from disease. Acute and chronic dysentery were referred to as fluxes and eruptive fevers were the diseases of small pox, measles and scarlet fever. Gangrene is not mentioned in the official records because at the time it was not considered a disease but the result of an operation. It is now known that gangrene is a result of a unique organism and qualifies as a disease.

Surgeons attempted to treat these conditions with a variety of compounds and treatments. Usually the most effective medicine was a good diet and the body’s natural restorative ability. The medical thought of the time believed that the blood carried disease and by purging the “ill-humors” in the blood, health could be restored. It would not be until the Second World War and the advent of antibiotics (primarily penicillin) that a real understanding and effective treatment of disease would be realized.

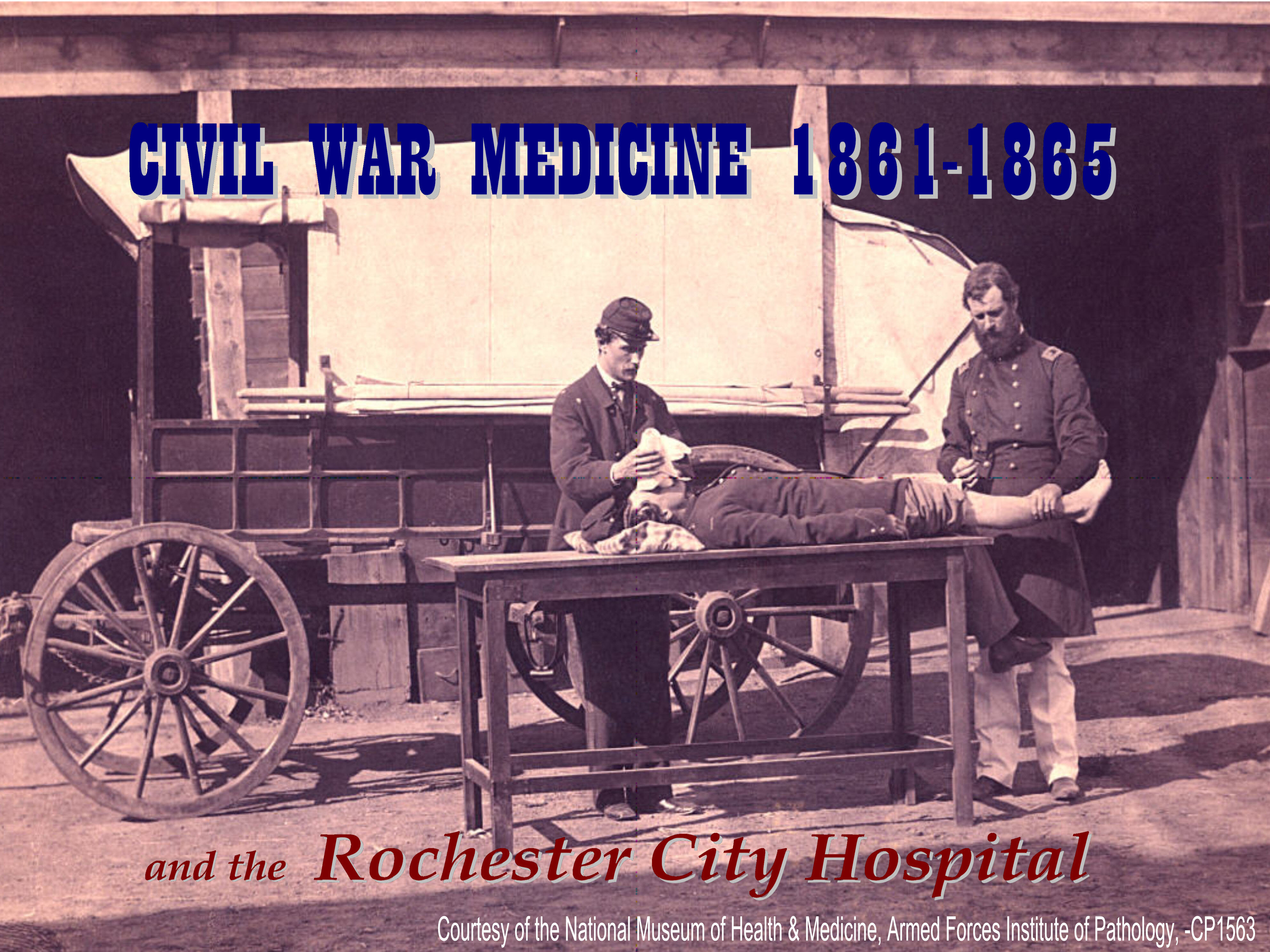

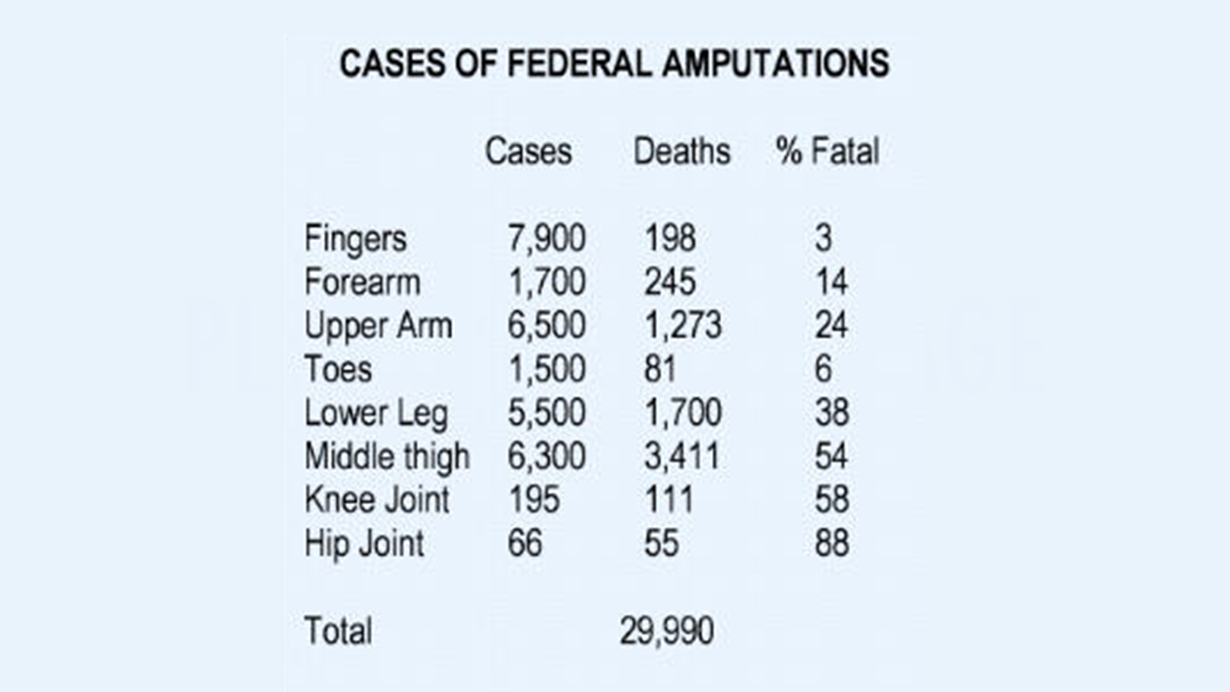

Battlefield Surgery

The most common surgical procedure performed by Army surgeons was amputation. The advancement of military weaponry far outpaced the advancement of medicine. The development and use of the .58 caliber Minié Ball bullet and the relatively low muzzle velocity of the percussion musket all but guaranteed the shattering of bones that left no alternative treatment but amputation. Although ether was used at times, chloroform was the most common form of anesthetic. A typical army surgical team would consist of one surgeon to perform the operation, two assistant surgeons to hold the patient on both sides and one assistant surgeon or medical assistant to hold the limb to be removed. It is estimated that after a major battle, each team would perform an amputation every 15 minutes and often, surgeons would remain on their feet engaged in surgeries for up to 48 hours at one stretch.

Rochester City Hospital's Army Surgeons

Service in the Army offered a unique opportunity for physicians to gain practical and clinical experience without the challenges associated with private practice. Several early members of the City Hospital’s medical staff served as Army surgeons and would later have significant influence on the hospital success and growth.

Doctor David Little began his medical practice in Rochester in 1859. Weeks after the guns of Fort Sumter sparked the beginning of the war, Little was mustered into the Army with the 13th N.Y. Volunteer Infantry in May 1861. He served for the next two years before being discharged in May 1863. Dr. Little returned to Rochester to resume his medical practice and was appointed as a visiting Physician to the staff of the City Hospital in October 1866. He later served as President of the Medical Staff from 1886 until 1898.

Immediately after his graduation from the Albany Medical College, Dr. Enoch Vine Stoddard enlisted as the Assistant Surgeon in the 65th N.Y. Volunteer Infantry in June of 1863. He served with the regiment at the battle of Gettysburg and through General Grant’s Virginia Campaign. After his discharge in September 1864, He returned home to resume his medical practice and later moved to Rochester in 1871. Dr. Stoddard was elected later that year as an attending physician at the Rochester City Hospital and served as Secretary of the Medical Staff from 1872 until 1898. In association with Doctors Whitbeck and Ely, Stoddard was responsible for the funding and construction of the Doctor’s Pavilion for Contagious Diseases at the hospital. One of his later distinctions was as founder of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Dr. William S. Ely was a second generation physician at the Rochester City Hospital. His father, William W. Ely, MD, was an early leader at Rochester City Hospital. After graduating from the University of Rochester in 1857, William S. Ely began the study of medicine in his father’s office. In August 1862 he enlisted in the 108th N.Y. Volunteer Infantry receiving his commission the following month as a regiment’s Assistant Surgeon. He was later transferred to Annapolis, Maryland where he served as an Army hospital administrator for the remainder of the war.

After three years of service, he was discharged in October 1865. Returning to civilian life, Dr. Ely enrolled in the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City, eventually graduating two years later. He received an appointment to the medical staff of the City Hospital in 1868 and for the next forty years his work at the city hospital would be instrumental in establishing the first School of Nursing, the Out-patient Department, and the Magne-Jewell memorial building. His career at the hospital and in the community also encompassed service as a private and ward physician and advisor to the managing Boards, hospital officers, colleagues, and as the first Vice-President of the Board of trustees of the University of Rochester.

Another member of the City Hospital’s staff to serve in the Civil War was Doctor Charles E. Rider. He received his medical degree from the University of Vermont in 1863 and a year later relocated to Rochester to establish his medical practice. Dr. Rider accepted the position as the City Hospital’s first Resident Physician in 1864 and later that year received appointed as Assistant Surgeon of the 54th Regiment of the N.Y. National Guard. The unit was activated for 90 days in July 1864 serving as prison guards in Elmira, N.Y. Returning to the City Hospital in November, Dr. Rider later developed the hospital’s first specialty clinic, the Department of Eye and Ear Disease. His work with the hospital laid the foundation for the hospital’s Out-Patient department where free medical treatment was dispensed. Dr. Rider remained active with the hospital until his death in 1909.

The American Civil War influenced the advancement of medical science by the shear magnitude of battle casualties. The lessons learned by the battle tested physicians and hospital administrators would later play a major part in the success and development of the early Rochester City Hospital.

Notes:

1. Teresa K. Lehr and Philip G. Maples, To Serve the Community: A Celebration of Rochester General Hospital 1847-1997 (Virginia Beach: Donning Publishing, 1997), 25-26

Credits: Text, and Layout:

- Robert Dickson

Research:

- Robert Dickson, Philip G. Maples and Wayne Mabb

Special Thanks to:

- Philip G. Maples and Kathleen E. Britton for research assistance and editorial comment.

Sources:

- Adams, George Worthington. Doctors in blue: The Medical History of the Union Army in the Civil War. Dayton: Morningside Press, 1985.

- Coco, Gregory A. A Vast Sea of Misery: A History and Guide to the Union and Confederate Field Hospitals at Gettysburg, July 1- November 20, 1863. Gettysburg, Pa.: Thomas Publishing, 1988.

- Dammann, Gordon. Pictorial Encyclopedia of Civil War Medical Instruments and Equipment. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing, 1983.

- McNamara, Robert F. St. Mary’s Hospital and the Civil War. Rochester: St. Mary’s Hospital,1961.

- Naythons, Matthew , Sherwin B. Nuland, Stanley B. Burns. The Face of Mercy: A Photographic History of Medicine at War. New York: Random House, 1993.

- Rochester In the Civil War, Blake McKelvey, ed. Rochester: Rochester Historical Society Publications XXII, 1944.

- Rochester City Hospital Collection, Baker-Cederberg Museum and Archives. Viahealth Archives Consortium, Rochester, N.Y.

Local Soldiers

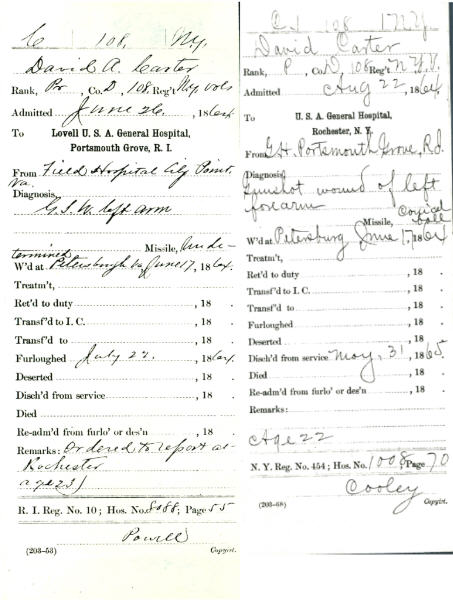

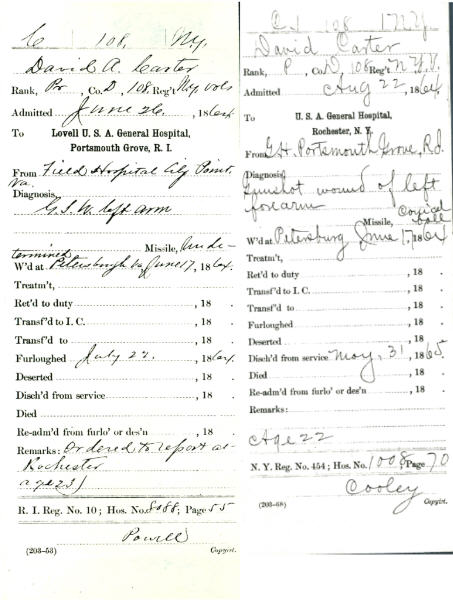

Many local soldiers from the surrounding communities were treated at the City Hospital. The below listed individuals are just four examples of soldiers sent back to their local communities to convalesce from their wounds.

Sources:

Teresa K. Lehr and Phillip G. Maples, To Serve the Community: A Celebration of Rochester General Hospital 1847-1997 (Virginia Beach: Donning Publishing, 1997), 42

Hospital Designs

The devastating British deaths from disease during the Crimean War prompted improvements in sanitation and hospital design during the Civil War. The belief that improved air ventilation minimized the spread of diseases led to the development of new designs in hospitals where patients could be separated by type of injury or illness, thereby minimizing the spread of disease and infection.

Florence Nightingale first suggested that military hospitals be built as pavilions.[1] These pavilions consisted of long separate wards that allowed for greater air ventilation and improved efficiency in treating similarly injured or diseased patients. By the end of the war, the pavilion style had become the predominate style for General Hospitals. Pavilions were designed to offer the benefits of a tent with the protection of a solid structure. They were lighter, warmer, and better ventilated and were approximately 150 feet long, 25 feet wide, with a 12 to 14 foot ceiling. Each pavilion ceiling had a series of adjustable shutters on the ridge of the roof that allowed ample ventilation yet protection from inclement weather. They were often connected by a common passageway that allowed quick access by hospital staff to any pavilion ward.

[1]. Matthew Naythons, MD, The Face of Mercy: A Photographic History of Medicine at War (New York: Random House, 1993), 62

Regimental Dressing Stations

The initial treatment of wounded soldiers was usually administered at regimental dressing stations that were located close to the battle lines and protected by earthworks or other natural defenses. These stations were typically manned by one Regimental Assistant Surgeon and one or two medical attendants. The wounded would either come to the dressing station or be helped there by comrades. Wounds were treated with rough dressings and whiskey and opium pills would be administered to ease pain. Ideally, each regiment was assigned six ambulances with six drivers and twelve stretcher bearers that would evacuate the wounded to the Division field hospital.

St Mary's Hospital

St Mary’s became Rochester’s first functioning hospital when it opened its doors on September 17, 1857. The first union soldiers were received at the hospital in 1862, although it would not be until March of 1863 that St. Mary’s would be officially designated a federal “Army General Hospital.” In spite of its official status, by the end of 1863, the hospital had admitted relatively few wounded soldiers most likely due to the high cost of transporting the wounded from the battlefields to western New York. The district U.S. Surgeon and military inspector, Dr. Azel Backus, advised the Nuns at the hospital to prepare to receive a hundred soldiers in the near future but the federal authorities ordered the soldiers back to their original hospitals. Rochester’s city leaders agreed with Dr. Backus that western New York soldiers would far better in a western New York hospital and consequently sent a local delegation to Washington in May 1864 to make their case to the U.S. Surgeon General. Shortly after, official word was received to prepare to receive at once up to three hundred sick and wounded soldiers. On June 7, 1864, the afternoon train delivered 375 wounded soldiers to Rochester, 60 of which were sent to the Rochester City Hospital and the remaining were admitted to St. Mary’s. [1]

In February 1865, there were 398 union soldiers under treatment at St. Mary’s. Over the course of the hospital’s military service, the hospital’s facilities and resources were often overloaded. Frequently, corridors were utilized for patients and tents were pitched on hospital grounds to accommodate the monthly influx of wounded soldiers. Many invalid soldiers came to the hospital in pitiful and desperate states of health. A number of released prisoners from the infamous Andersonville Prison made their way to St. Mary’s in a condition described as “living dead”. Most were nursed back to health “through the patient efforts of the Sisters of Charity.” [2] Appeals to the community for food and supplies were often rewarded with generous donations.

It is difficult to accurately say how many soldiers were treated by St. Mary’s during the Civil War years. Some estimates have claimed four or five thousand patients but the remaining ledgers, evidence, and the final report by the hospital sent to Albany in December 1866 reports that there were “soldiers treated, 2500.”

[1]Robert F. McNamara, St. Mary’s Hospital and the Civil War, Rochester: St.Mary’s Hospital, 1961

Depot Evacuation Hospitals

By 1863, regional evacuation depots were established to process the large number of casualties. As with the division and Corps hospital systems, one medical officer would command the depot and several subordinate medical officers were delegated management of key departments within the organization such as food and shelter, Military administration, and supply replenishment. Each depot was organized into Corps hospitals consisting of Division hospitals.

In 1864, the City Point Depot merged the five army corps of the Army of the Potomac effectively caring for 6,000 to 10,000 patients. The hospital wards consisted of log buildings, called pavilions, of approximately 20 feet wide by 50 feet long. The hospital eventually grew to 90 pavilions and 324 additional tents. It was outfitted with iron beds, steam water pumps, and a steam laundry operated by former slaves. Mosquito nets for the beds defended against the swarms of flies drawn by the open latrines. Each Corps hospital operated its own dispensary, commissary store house, and general and special diet kitchens. Wounded soldiers would either convalesce there then return to their regiments or be evacuated to one of the many general hospitals established throughout the north.

Division and Corps Hospitals

The Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, Dr. Jonathan Letterman, organized the Army into a system of Divisional hospitals in October 1862. This system of organization and management eventually spread throughout the Federal Army.

Commanded by one medical officer rather than a line officer, it consisted of four operating teams of three surgeons each and numerous medical attendants and support staff. Each hospital carried sufficient medical supplies to house and care for a typical division of 7,000-8,000 personnel. Division surgeons performed more thorough examinations and treatment of wounds and emergency surgeries. A large portion of surgeries were postponed until reaching the much larger Depot evacuation hospitals. At the end of the day’s campaigning, each division hospital set up what was referred to as a “Ambulance hospital” that treated minor wounds and common illness’ such as sunstroke and diarrhea. Division hospitals were organized into centrally located Corps Hospitals consisting of three to four divisions.

Federal General Hospitals

The title of U.S. Army General Hospital was designated because admissions were not confined to any particular military unit or post unlike Division or Corps Hospitals. By the end of the war, General hospitals were established in scores of eastern cities. Washington was the center of military medicine due to its close relation to the war department and its close proximity to the majority of combat in the later years of the war. Its 16 General Hospitals provided close to 30,000 beds and only Philadelphia would rival Washington’s importance. In March 1865, Philadelphia maintained 27 hospitals and 25,000 beds. Here in Rochester, only St. Mary’s Hospital was designated as an Army General Hospital, although both St. Mary’s Hospital and the Rochester City Hospital admitted and treated wounded soldiers.

During the four years from 1861-1865, General Hospitals treated 1,057,523 soldiers with a mortality rate of only eight percent, the lowest ever recorded for military hospitals and lower than many civilian counterparts.

Local Soldiers

Many local soldiers from the surrounding communities were treated at the City Hospital. The below listed individuals are just four examples of soldiers sent back to their local communities to convalesce from their wounds.

Sources:

Teresa K. Lehr and Phillip G. Maples, To Serve the Community: A Celebration of Rochester General Hospital 1847-1997 (Virginia Beach: Donning Publishing, 1997), 42

Hospital Designs

The devastating British deaths from disease during the Crimean War prompted improvements in sanitation and hospital design during the Civil War. The belief that improved air ventilation minimized the spread of diseases led to the development of new designs in hospitals where patients could be separated by type of injury or illness, thereby minimizing the spread of disease and infection.

Florence Nightingale first suggested that military hospitals be built as pavilions.[1] These pavilions consisted of long separate wards that allowed for greater air ventilation and improved efficiency in treating similarly injured or diseased patients. By the end of the war, the pavilion style had become the predominate style for General Hospitals. Pavilions were designed to offer the benefits of a tent with the protection of a solid structure. They were lighter, warmer, and better ventilated and were approximately 150 feet long, 25 feet wide, with a 12 to 14 foot ceiling. Each pavilion ceiling had a series of adjustable shutters on the ridge of the roof that allowed ample ventilation yet protection from inclement weather. They were often connected by a common passageway that allowed quick access by hospital staff to any pavilion ward.

Regimental Dressing Stations

The initial treatment of wounded soldiers was usually administered at regimental dressing stations that were located close to the battle lines and protected by earthworks or other natural defenses. These stations were typically manned by one Regimental Assistant Surgeon and one or two medical attendants. The wounded would either come to the dressing station or be helped there by comrades. Wounds were treated with rough dressings and whiskey and opium pills would be administered to ease pain. Ideally, each regiment was assigned six ambulances with six drivers and twelve stretcher bearers that would evacuate the wounded to the Division field hospital.

St Mary's Hospital

St Mary’s became Rochester’s first functioning hospital when it opened its doors on September 17, 1857. The first union soldiers were received at the hospital in 1862, although it would not be until March of 1863 that St. Mary’s would be officially designated a federal “Army General Hospital.” In spite of its official status, by the end of 1863, the hospital had admitted relatively few wounded soldiers most likely due to the high cost of transporting the wounded from the battlefields to western New York. The district U.S. Surgeon and military inspector, Dr. Azel Backus, advised the Nuns at the hospital to prepare to receive a hundred soldiers in the near future but the federal authorities ordered the soldiers back to their original hospitals. Rochester’s city leaders agreed with Dr. Backus that western New York soldiers would far better in a western New York hospital and consequently sent a local delegation to Washington in May 1864 to make their case to the U.S. Surgeon General. Shortly after, official word was received to prepare to receive at once up to three hundred sick and wounded soldiers. On June 7, 1864, the afternoon train delivered 375 wounded soldiers to Rochester, 60 of which were sent to the Rochester City Hospital and the remaining were admitted to St. Mary’s. [1]

In February 1865, there were 398 union soldiers under treatment at St. Mary’s. Over the course of the hospital’s military service, the hospital’s facilities and resources were often overloaded. Frequently, corridors were utilized for patients and tents were pitched on hospital grounds to accommodate the monthly influx of wounded soldiers. Many invalid soldiers came to the hospital in pitiful and desperate states of health. A number of released prisoners from the infamous Andersonville Prison made their way to St. Mary’s in a condition described as “living dead”. Most were nursed back to health “through the patient efforts of the Sisters of Charity.” [2] Appeals to the community for food and supplies were often rewarded with generous donations.

It is difficult to accurately say how many soldiers were treated by St. Mary’s during the Civil War years. Some estimates have claimed four or five thousand patients but the remaining ledgers, evidence, and the final report by the hospital sent to Albany in December 1866 reports that there were “soldiers treated, 2500.”

[1]Robert F. McNamara, St. Mary’s Hospital and the Civil War, Rochester: St.Mary’s Hospital, 1961

Depot Evacuation Hospitals

By 1863, regional evacuation depots were established to process the large number of casualties. As with the division and Corps hospital systems, one medical officer would command the depot and several subordinate medical officers were delegated management of key departments within the organization such as food and shelter, Military administration, and supply replenishment. Each depot was organized into Corps hospitals consisting of Division hospitals.

In 1864, the City Point Depot merged the five army corps of the Army of the Potomac effectively caring for 6,000 to 10,000 patients. The hospital wards consisted of log buildings, called pavilions, of approximately 20 feet wide by 50 feet long. The hospital eventually grew to 90 pavilions and 324 additional tents. It was outfitted with iron beds, steam water pumps, and a steam laundry operated by former slaves. Mosquito nets for the beds defended against the swarms of flies drawn by the open latrines. Each Corps hospital operated its own dispensary, commissary store house, and general and special diet kitchens. Wounded soldiers would either convalesce there then return to their regiments or be evacuated to one of the many general hospitals established throughout the north.

Division and Corps Hospitals

The Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, Dr. Jonathan Letterman, organized the Army into a system of Divisional hospitals in October 1862. This system of organization and management eventually spread throughout the Federal Army.

Commanded by one medical officer rather than a line officer, it consisted of four operating teams of three surgeons each and numerous medical attendants and support staff. Each hospital carried sufficient medical supplies to house and care for a typical division of 7,000-8,000 personnel. Division surgeons performed more thorough examinations and treatment of wounds and emergency surgeries. A large portion of surgeries were postponed until reaching the much larger Depot evacuation hospitals. At the end of the day’s campaigning, each division hospital set up what was referred to as a “Ambulance hospital” that treated minor wounds and common illness’ such as sunstroke and diarrhea. Division hospitals were organized into centrally located Corps Hospitals consisting of three to four divisions.

Federal General Hospitals

The title of U.S. Army General Hospital was designated because admissions were not confined to any particular military unit or post unlike Division or Corps Hospitals. By the end of the war, General hospitals were established in scores of eastern cities. Washington was the center of military medicine due to its close relation to the war department and its close proximity to the majority of combat in the later years of the war. Its 16 General Hospitals provided close to 30,000 beds and only Philadelphia would rival Washington’s importance. In March 1865, Philadelphia maintained 27 hospitals and 25,000 beds. Here in Rochester, only St. Mary’s Hospital was designated as an Army General Hospital, although both St. Mary’s Hospital and the Rochester City Hospital admitted and treated wounded soldiers.

During the four years from 1861-1865, General Hospitals treated 1,057,523 soldiers with a mortality rate of only eight percent, the lowest ever recorded for military hospitals and lower than many civilian counterparts.